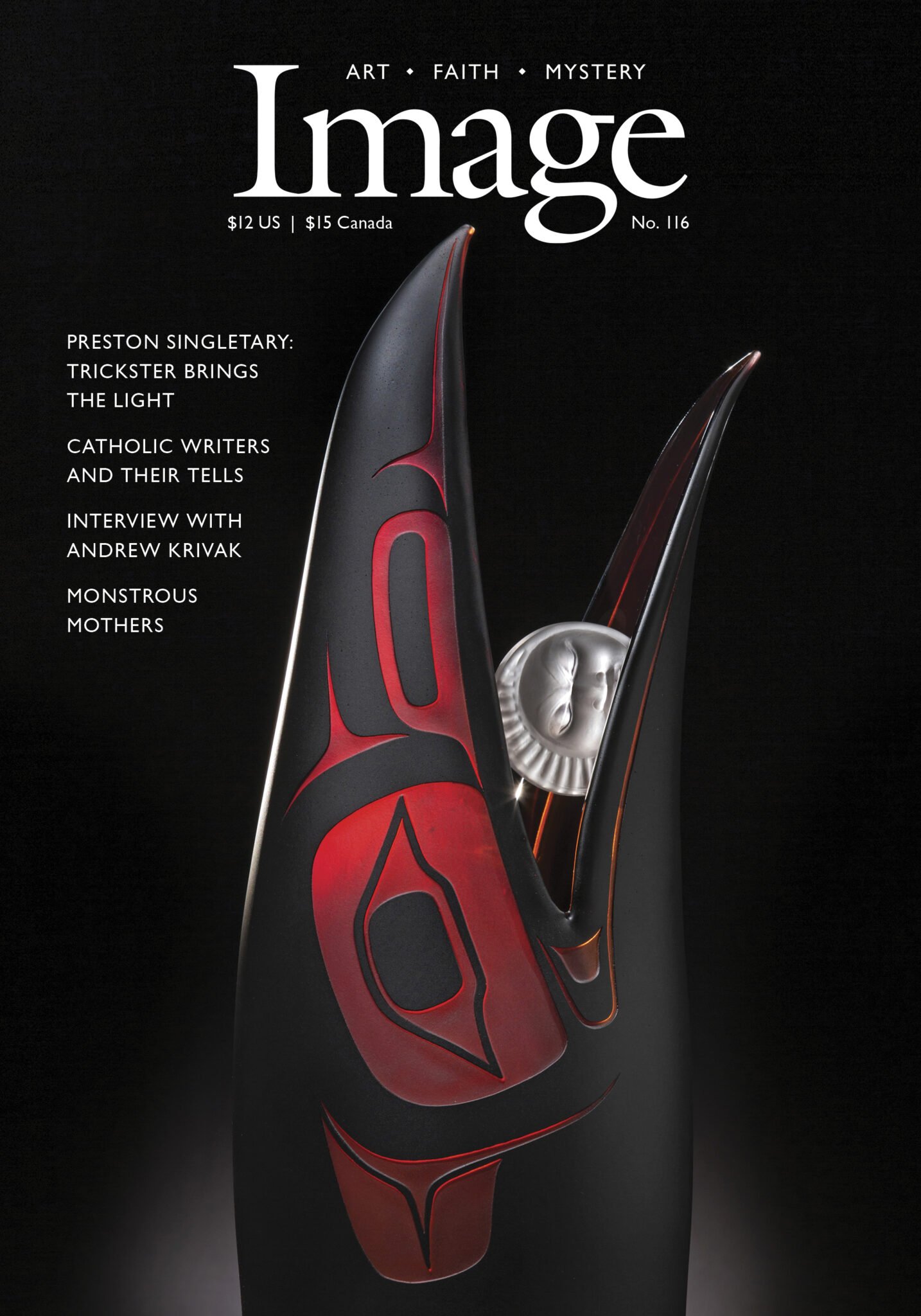

Raven Steals the Sun

Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

Preston Singletary, Raven cover image

THE STORY GOES LIKE THIS:

A long time ago, the raven looked down from the sky and saw that the people of the world were living in darkness. The ball of light was kept hidden by a selfish old chief. So the raven turned itself into a spruce needle and floated on the river where the chief’s daughter came for water. She drank the spruce needle. She became pregnant and gave birth to a boy which was the raven in disguise. The baby cried and cried until the chief gave him the ball of light to play with. As soon as he had the light, the raven turned back into himself and carried the light into the sky. From then on, we no longer lived in darkness.

In many ways it really is the first story, a redemption narrative that also includes creation, incarnation, transubstantiation, and apocalypse, but it’s also the first version I heard of a story I would hear again many times.

The trickster-raven cycle is a kind of ur-story for tribes native to the Pacific Northwest, as ubiquitous among those groups as Noah’s ark is among some others. I first encountered it in junior high after my family moved to Washington State. It has traveled well beyond those bounds too, wandering in and out of other stories like some curious bird.

In poems, every word matters. In holy Scripture, the Word is what matters. But here, though the language and idiom may change with time and taste, the cycle is what matters. Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

At the Tacoma Museum of Glass, when I saw Preston Singletary’s Raven and the Box of Daylight, a show that has since traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian and earned heaps of praise from critics, the feeling I had was of what E.T.A. Hoffmann would have called the uncanny: the familiar in the strange, or the strange in the familiar. It’s what we feel when looking at a stranger we think we recognize or hearing a remixed version of a song long cherished. I walked through the show enraptured, but with a constant nagging sense of déjà vu.

It wasn’t that the raven cycle so beautifully maps onto the Christian story of self-sacrifice and redemption—a mapping that is not, I think, a matter of cultural appropriation so much as of two cultures working toward and finding the same truth about the structure of the universe and the human heart. Rather, between those glass monoliths, the words of the familiar raven story were there, and they were different. Singletary had taken a story I’d cherished for twenty-some years, one that I’d memorized, and made it fresh.

Read the essay over at Image…