Gathers his Inheritance: Buechner on Houses and OZ

Frederick Buechner’s “Entrance to Porlock” is a meditation on the oddness of generosity, and on Coleridge, and flying houses.

Toward a Resurection Aesthetic

He practiced jumping, getting big, breaking some bricks with his head. And then he fell down one of those mine shafts they have everywhere and died…

“But you have another life,” I said. “Look at those hearts.”

Exit, Pursued by a Presbyterian

Some critics, theater-goers, and directors enjoy this scene simply because it seems so random: here we are in a very serious play about jealousy and power imbalance, rage and injustice, gift-economy and indebtedness and now this crazy bit of text suggesting, what exactly?

Why I Go to Church

Church is a lot of things for me: the center of my social and artistic life, the place I practice my actual talents, for music, for leadership—but I love it in part because I’m a weakling who can hardly stand to stand up most mornings and the church was made for, and needs, people like me.

Raven Steals the Sun

Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

The Life and Afterlife of "Festus"

Philip James Bailey’s Festus is the most popular poem most people have never heard of.

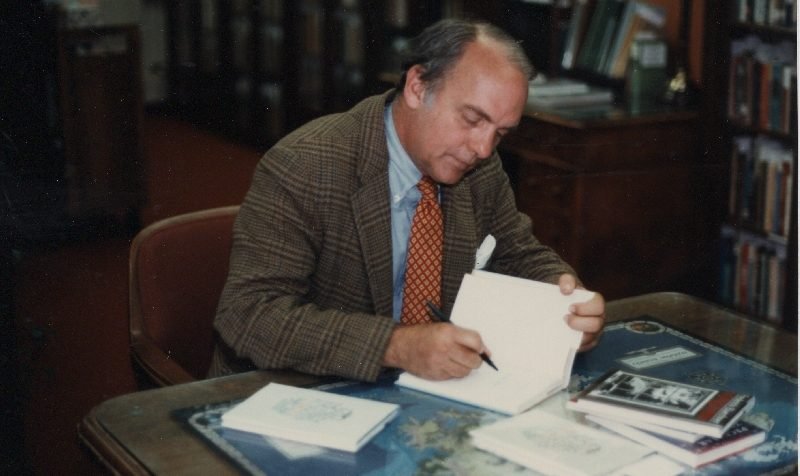

Remembering Frederick Buechner

Just about every artist of faith I know — photographers, poets, actors — all count his books as among their dearest treasures.

Changes and Chances in Literary Pedagogy

English departments at Christian liberal arts institutions have faced a broadband array of economic and cultural challenges in recent years, but I’m optimistic.

Small Letters and Sparrows

What qualifies as a miracle worth recounting? And how far beyond the probable does an event need to be before we consider it miraculous?

4 Simple Ways to Help Your Most-Disconnected Students

Faculty members have a key role to play in retaining students, to the benefit of both.

Joy of Every Longing Heart

But what if we think about a different shape for Advent, one that builds slowly toward Christmas in a gradual way–she’s pregnant! There’s the star!– that Christmas day is a punctuation, the celebration, all our hopes come true at last, and then Christmastide is the season of reflection there-following?

Still Life with Wine and Occasional Fires

Normally, though still a frenzy, my writing has built-in speed bumps, to keep the crystal from jittering around.

Humanities Research with Undergraduates

Admissions brochures routinely tout the benefits of small class sizes, with pictures of lab-coated undergraduates doing beaker work alongside science professors in safety goggles. I’ve always wondered: Is the research, like the image, staged or real?

6 Black Protest Poets

In times of increasing racial tensions, it can be difficult to know what to do with one’s anger, righteous or otherwise. And it can be just as difficult to know where to get an honest picture of the worldviews of people we may consider, for whatever combination of reasons, “other.”

The Life-Changing Magic

I want for them a sense of super-abundance borne not of the horde of possessions on which they rest, but of the competence and creativity they are even now developing, the sense that they can do without some things, can toss whole essays into the rubbish bin if they need to.

5 Contemporary Poets Christians Should Read

I’m always a little sad after a poetry reading when someone comes up and tells me they’re “really into Christian poets,” and when I ask excitedly “which ones?” they rattle off a short list that ends with Gerard Manley Hopkins or George Herbert

The Christological Vision of Pirates of the Caribbean

The curse, the risen dead, the rightful captain, the man who does the waking, the island, and the great adventure all exist independently of her belief. She doesn’t get to create her reality, as none of us do, but is instead a character in someone else’s high seas adventure.

Mistrusting C.S. Lewis

I suspect that, casting about for firm ground on which to stand in the absence of a reliable canonicity of taste, scholars hold up as a final source that one source they take to be originary as the end of discussion.

The Quietest Painting in the Room

Matthew is about to get created in the exchange just the way Adam was, is about to come alive to himself and to history in a way no one, least of all this poor, pantalooned sop, had imagined a few coins ago.