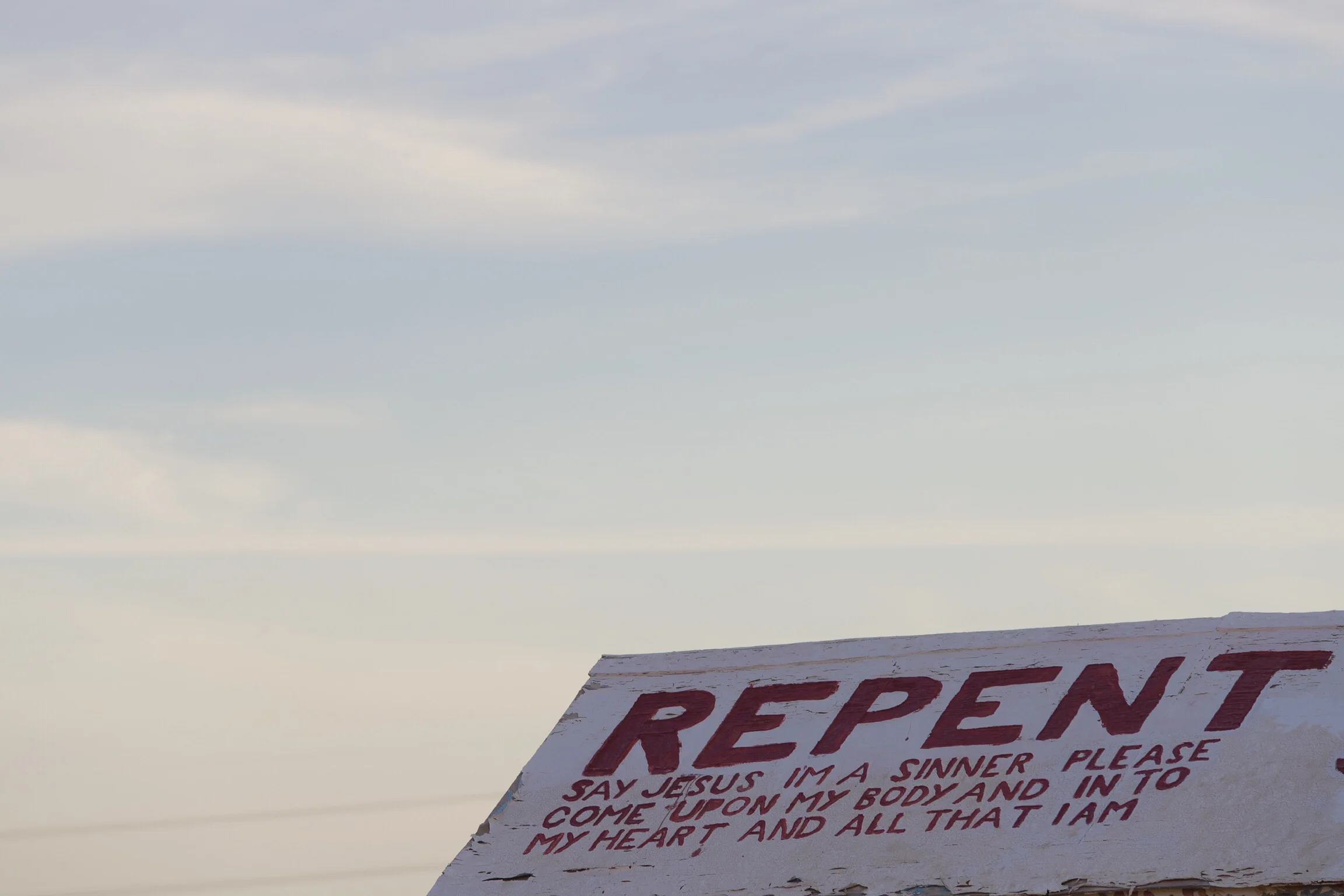

Lucifer's Homily

Lucifer here has just found out the the world is going to end; not someday, but in the next month or so, and is trying his hand at warning people, knowing, through long experience, that they will do nothing to change their lives.

Scottish Literature Course

Among the many assignments for the course on Scottish Literature I taught in Winter term for the University of Washington, my favorite was the creation of a Complete Works of Alexander Smith. mith (1830-1867) is a marvelously gifted poet of the Scottish working class who exploded onto the worldwide literary scene in the 1850's and was hardly ever heard from again, despite pleas every 30 years or so, by someone who actually read his work, for people to appreciate his genius. (For more on this phenomenon from a scholarly angle, see LaPorte and Rudy eds. Special Edition of Victorian Poetry vol. 42.4 2004) The pleas are ignored of course, and nothing of Smith's has been in print for 100 years. As a class, we took it upon ourselves to make a scholarly edition, (of James Thomson B.V., in another section) complete with introductions and footnotes, transcribing from scanned manuscripts where necessary.